(2022-11-30) Nadia Mapping Out The Tribes Of Climate

Nadia Asparouhova: Mapping out the tribes of climate. Climate is a gravity well for talent, but why don’t other, equally impactful topics attract talent in the same way? Why isn’t everyone dropping everything to work on homelessness, or global poverty, or curing cancer?... What I found instead is that while the media still portrays climate change as a simple question of beliefs, the climate field has long moved on to diversified solutions. Whether one believes in climate change is no longer the interesting question; now it’s “What do you think is the right approach?”

I think I learn toward the "Climate urbanism", "climate tech", and "eco-globalism" tribes.

Climate is frequently coded as a left-leaning issue, but there are also centrist and right-leaning people who operate in different factions

Nor do climate people all agree on the right solutions to pursue. In some cases, they believe other tribes are actively harmful to their cause.

it seems to me that climate is better understood not as a singular list of technology and policy action items, but as an assortment of climate tribes. Tribes tell us why these opportunities are interesting and help us make better predictions about how they will unfold.

Ultimately, I landed upon seven climate tribes, which I’ll expand on in a bit:

I’ll also add a requisite note that this analysis is heavily centered on American climate trends

Climate change isn’t about evangelism anymore

In the 1980s, climate change (then referred to as global warming) received little attention outside of scientific communities

By the 1990s and early 2000s, climate change began to escape from scientific communities into the public domain... Al Gore... giving his presentation about climate risk – captured in the 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth – over 1,000 times.

The documentary had a profound impact on John Doerr, who, along with his venture capital firm, Kleiner Perkins, became the face of the cleantech movement in the early 2000s

At the time, the messages from climate evangelists like Gore and Doerr were less sophisticated about solutions and more about getting people to care about global warming in the first place

Today, however, it’s safe to say that climate change has won the battle for mindshare

Most of this change in public sentiment appears to come from converting the “Concerned” and “Cautious” groups to “Alarmed”, rather than the disinterested groups, which remained roughly unchanged

Climate change has now progressed beyond an early evangelism phase and into the solutions phase. Despite this development, however, media coverage about climate lags behind

Michael Crichton delivered a series of eloquent talks about environmentalism and religion.

I also wonder whether the “science versus religion” narrative is still relevant in today’s landscape. Crichton himself stated that he thinks “you cannot eliminate religion from the psyche of mankind. If you suppress it in one form, it merely re-emerges in another form

If religious tendencies cannot be repressed from our collective psyches, why not start with the premise that climate is a religion, then try to understand it on those terms? Instead of insisting that we “stick to science” or only focus on technology, we can instead evaluate climate opportunities through the lens of tribal values. (This might predict who you'll be able to stand working with, but it doesn't predict the usefulness of tribe's solution! On the other-other hand, a solution which is useful but doesn't get adoption doesn't do any good.)

I noticed that there was very little doomer talk amongst people who actually work in climate. If anything, they seemed quite optimistic. This makes sense if you think about it: why would you work in a doomer industry if you thought there was no hope?

If people who work in climate aren’t doomers, I tried to figure out how they ended up there instead

I noticed two major personas:

- Incumbents: People with specialized skills who have been working in relevant industries for awhile

- Switchers: People with generalized skills who switched into climate (frequently those with a background in tech, finance, management consulting, or corporate executives)

Climate incumbents are more likely to be driven by personal curiosity

Climate switchers, on the other hand, usually don’t have backgrounds in anything climate-related

Many explicitly state that climate is a way to do something “more impactful” with their careers, which provides them with deeper meaning than, say, managing employees at a Fortune 500 company or selling SaaS products.

Climate switchers are attracted to problems they know how to fix: they will often apply their existing skills, such as data engineering or compliance, towards climate, rather than acquire new skills.

The strategies pursued by climate switchers are informed by their professional backgrounds and what they’ve seen work in their careers, which ultimately leads to the formation of different climate tribes. Climate tech types, for example, might look for unexplored technology gaps to commercialize, whereas eco-globalist types will focus more on regulation and measuring risk.

Doomerism serves a general PR purpose, even if it’s annoying

The climate tribes of today

Also note that the people, orgs, and keywords mentioned here are non-comprehensive lists – think of them more as assorted ephemera, meant to evoke the aesthetic (vibe) of that tribe.

Energy maximalism

Their goal is to develop technology and policy that makes it possible to have endless energy

they argue that energy abundance is directly correlated to economic growth, and that industry and policy have been overly focused on limiting rather than unlocking more energy.

Many people in this tribe are affiliated with ecomodernism, an umbrella philosophy that takes an anthropocentric view of the environment

While many energy maximalists support nuclear as part of a broader energy portfolio, a subset could be called nuclear maximalists

Relevant people and orgs: Eli Dourado, Austin Vernon, Mark Nelson, Breakthrough Institute, Tim Latimer, Michael Shellenberger, Isabelle Boemeke

Climate urbanism

Climate urbanists envision a densely populated world that’s harmoniously networked, industrious, and resilient to climate threats. Cities are the primary leverage point for their solutions, reflecting both a global trend towards urbanization,

It’s hard to know where exactly “urbanism” stops and “climate urbanism” begins

Lyn Stoler and Sonam Velani recently introduced the term “climate industrialism”, which they describe as an “optimistic, action-oriented response.” Like energy maximalists, they believe climate solutions are directly correlated with economic growth

Areas of interest: Infrastructure, transportation, construction, energy transmission, climate adaptation, renewable energy

Related movements: Urbanism, solarpunk

Relevant people and orgs: Ezra Klein, Jesse Jenkins, Lyn Stoler, YIMBY, 2150.vc

Climate tech

believing that the last two decades of global negotiations have little to show for, and that we can instead move faster and more efficiently through the early-stage private sector – primarily, startups

Those in climate tech see policy as a means of unlocking innovation, rather than as a primary tool for change. The goal is to remove policy roadblocks, not add more (see, for example, the Institute for Progress’s paper on National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) reform, which argues that the environmental review process is “slowing down the clean energy transition”). Instead, they focus on innovating through commercial markets.

While energy maximalists skew more towards the R&D side of technology, climate tech operates more on the commercial side of the pipeline: bringing existing technologies to market

The carbon removal initiative Frontier, for example, released a “carbon removal (CDR) gap database”, highlighting major knowledge and innovation barriers to carbon removal.

Relevant people and orgs: Stripe Climate, Frontier, Nan Ransohoff, Shayle Kann, Lowercarbon Capital, Chris Sacca, Ryan Orbuch, Jason Jacobs, Climate Tech VC

Eco-globalism

This group is focused on regulation as the primary vehicle of change, with the goal of reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. Unlike the aforementioned tribes, eco-globalists take a scarcity approach to climate

eco-globalists are more likely to have a background in finance or management consulting

Interests: carbon offsets and credits; carbon pricing; carbon tax

Relevant people and orgs: World Economic Forum, UN Climate Change Conference (COPx), Bloomberg Green, Tom Steyer, John Doerr

Environmentalism

The environmentalists are the anti-corporate counterpart to the eco-globalists, and the modern descendants of “classic” environmentalism

Like eco-globalists, environmentalists focus on sustainability as the ideal outcome, but they’re more concerned with the impact of individual (rather than collective) actions, whether that’s holding Exxon accountable or reducing personal energy consumption.

Within environmentalism, there are two further sub-groupings

- Those focused on climate justice

- Degrowth

Relevant people and orgs: Sierra Club, Mother Jones, Grist, The Guardian, Hot Take, Assaad Razzouk, Leah Stokes, Mark Ruffalo, HEATED, Jason Hickel, Earthjustice

Neopastoralism

Neopastoralists believe that technology has corrupted our natural environment and that society is unraveling, followed by a rewriting of our political and social systems. Like doomers, they feel that the world is changing for the worse, but unlike doomers, they are in the “acceptance” rather than “anger” stage of grief

They are focused on climate adaptation, but from a self-preservation standpoint. They believe self-reliance is more important than coordinating with others, and prioritize protecting themselves and their loved ones.

Relevant people and orgs: Doomer Optimism, Willow Liana, Anarcho-Contrarian, Industrial Society and Its Future

Doomerism

Doomers believe there is no hope for the future

Doomers are largely disconnected from positive-sum climate efforts; their actions are centered around managing their subjective experience of the world.

Within this tribe, there are two major sub-types

- Introspective: focused on managing their emotions amidst external turmoil

- Externalized: channeling their anger into performative “shock” activism

Relevant people and orgs: Greta Thunberg, Extinction Rebellion, Just Stop Oil, Gen Dread

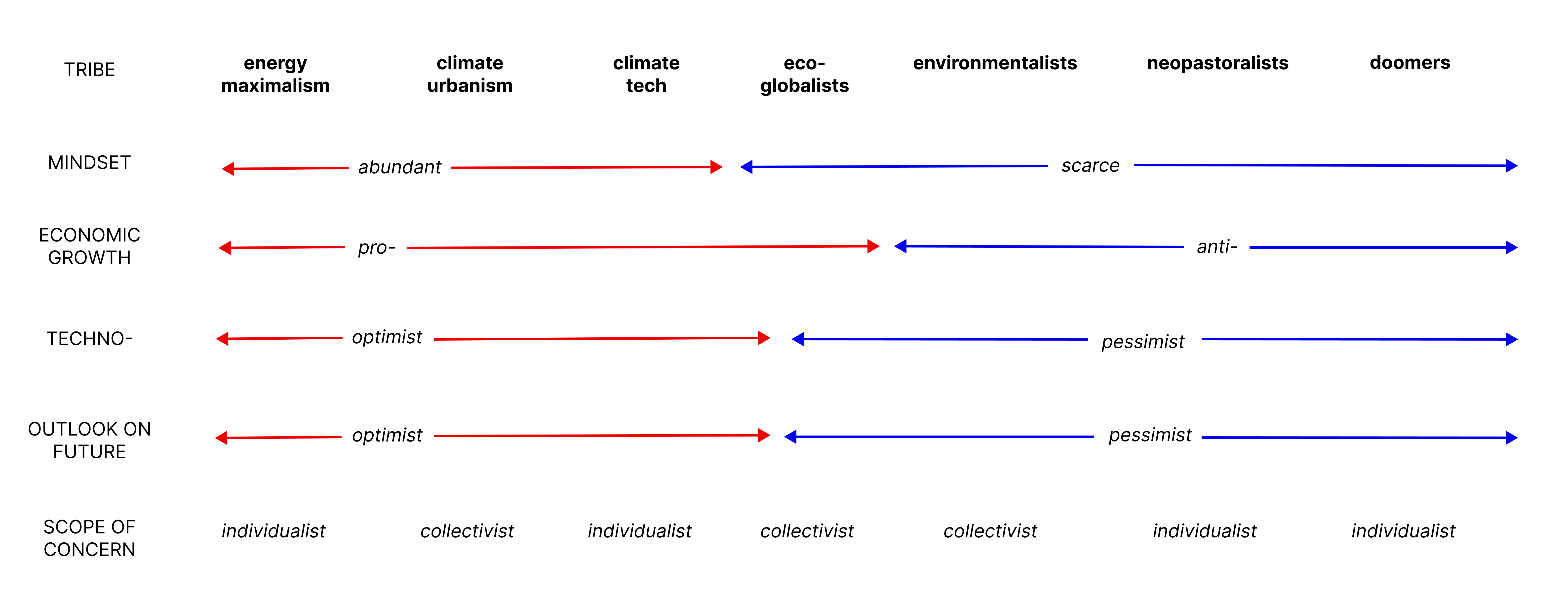

For a snapshot view, here are all the tribes, plotted along a few key parameters:

Finally, just to round out our landscape, here are a few other groups I considered including, but I think aren’t (yet?) quite full-fledged tribes:

- Climate escapists

- Regenerative finance

- Bobrossians

Okay, but really - which is the best climate tribe?

today’s climate world is more like a pluralistic landscape of tribes. Implicit in this reframing is a belief that there is no single “best climate solution” that needs to win out.

If climate is a parallel universe rather than a niche cause area, we ought to lean into the marketplace of ideas and encourage everyone to go work on the solution that speaks to them.

By the end of this research, I was surprised to find that I actually do have more of a stance on climate than I realized; I just needed to find a tribe that spoke to me.

Why do climate tribes matter? Tribes can help people find each other more quickly by communicating values instead of agendas

This rhymes with my conception of idea machines: a modern approach to turning ideas into outcomes by starting with a community, which only develops an agenda downstream of its values

Secondly, tribes are a better way of forecasting what the future looks like.

To use a simple example, the funding for climate tech versus eco-globalism comes from two very different places. In analyzing the long-term viability of climate work, we ought to consider not just macro conditions that might affect all tribes (such as the price of specific technologies), but also the risks associated with specific funding sources, which might lead one tribe to falter, while another one thrives.

Finally, the most important thing about climate tribes is that they shift the conversation from passive, “true-believer” narratives towards active, action-oriented ones

Addendum: ‘Doomer industries’ and the search for meaningful work

AI safety, biosecurity, global catastrophic risk, misinformation, and population decline (and its counterpart from a previous generation, overpopulation).

A doomer industry is the talent ecosystem that forms around a perceived civilizational threat (Existential Threat) that demands us to prioritize it, for the sake of humanity, over whatever else we might want to do instead. Doomer industries like climate and AI safety have a sort of wheedling, persistent mind-virus quality to them that other important topics – say, global poverty or education – do not.

is climate’s transformation from “social cause” to “doomer industry” indicative of some broader trend? Will we see speciation of doomer industries?

Michael Shellenberger posits that climate only took on an apocalyptic pall following two world wars and a Cold War, when we ran out of “real” doomer scenarios to be afraid of

someone like Shellenberger might say that the reason we have doomer industries is because, in a secularized world of comparative peace and prosperity, it fills the role of some primal human need for community. Preventing a doomsday scenario is a way to feel connected to millions of other people, all working towards the same purpose

Still, even in the post-Cold War version of environmentalism, climate didn’t become a widespread doomer topic until 2018

Unsurprisingly, 2018 coincides with a lot of other trends around political polarization and social media, which we might speculate caused doomer industries to make the leap from being niche cause areas to high-status types of work. I will attempt no further analysis here, as that seems beyond the scope of this (already very long) post, beyond pointing out that the widespread adoption of social media seems to coincide with a growing shift in how we define meaningful work

Here are a few common qualities I noticed:

Shared belief in a disaster scenario

For both climate and AI safety, I was surprised by the lack of consensus as to what, exactly, was going to happen and when, despite popular media portrayals of climate as an extinction-level event

It’s also interesting that both the climate and AGI apocalypses – two cause areas that should be completely unrelated – are thought to be roughly 30 years away

Adjacent to a business opportunity

Most cause areas struggle to attract talent, because there is no money to be made

Doomer industries, on the other hand, can attract high-quality talent because they are adjacent to some underlying commercial opportunity that either makes it possible to get paid well, or attracts the overflow from workers who already made money in the adjacent field and are now in the “second act” of their careers.

Fertile environment for idea generation and exchange

Edited: | Tweet this! | Search Twitter for discussion

Made with flux.garden

Made with flux.garden