(2025-12-16) ZviM The $140,000 Question

Zvi Mowshowitz: The $140,000 Question. There was a no good, quite bad article by Michael Green that went viral. (2025-11-23) Green Poverty Line Is A Lie

His actual claim in that post, which was what caught fire, was that the poverty line should be $140,000, and even that this number is him ‘being conservative.’

Obviously that is not remotely true, given that:

- America is the richest large country in history by a wide margin.

- $140,000 is at or above median household income.

- You can observe trivially that a majority of Americans are not in poverty.

Today’s post covers this narrow question as background, including Green’s response.

I’m writing this as a lead-in to broader future discussions of the underlying questions:

Table of Contents

- None Of This Makes Any Sense.

- Let’s Debunk The Whole Calculation Up Front.

- The Debunking Chorus.

- Okay It’s Not $140k But The Vibes Mean Something.

- Needing Two Incomes Has A High Cost.

- I Lied….

- …But That’s Not Important Right Now.

- Poverty Trap.

- Poverty Trap Versus Poverty Line.

- Double or Nothing.

None Of This Makes Any Sense

but he is correct that the official poverty line calculation also does not make any sense.

Neither number is saying a useful thing about whether people are barely able to stay afloat, or whether lives are getting better. My guess is the right number is ~$50,000.

The point of a poverty line is not ‘what does it take to live as materially well as the median American.’

Green literally equates the poverty line with median income, in two distinct ways. No, really. He equates this with ‘basic participation.’ That’s not how any of that works.

Poverty actually means (from Wikipedia) “a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living.”

Let’s Debunk The Whole Calculation Up Front

it makes even less sense than you think, as in it is actually tautological equating of median income with poverty except with calculation errors.

I mostly wrote my debunk before reading the others, but we found the same things, so if you’ve read the others you can skip this section and the next one.

The Debunking Chorus

A chorus rose up to explain this person being Wrong On The Internet. Here’s some pull quotes and overviews. Several of these links go into great detail, some would say unnecessary detail but those some would be wrong, we thank all of you for your service.

Okay It’s Not $140k But The Vibes Mean Something

Clifford Asness: The populist fabulists will only move the goal posts again

Needing Two Incomes Has A High Cost (two-income family)

This also leads into themes I mostly am saving for next time, but needs to be mentioned here: A family with one typical income will increasingly fall behind.

Falling behind doesn’t mean starving. Falling behind still sucks. A lot.

Real wages for married men are up, but the median income for married couples is up a lot more because a lot more women are working, which means if only the man works you’re falling behind. You get punched in the face with the Revolutions of Rising Requirements and Expectations.

Family incomes have been moving up, much of which is increased female labor participation but a lot less than all of it.

I Lied…

Green’s follow-up post might be the most smug and obnoxious ‘okay yes my original post was full of lies but I don’t care because it worked to get the discussion I wanted

I mean, sir, that’s because your facts were wrong and your arguments were nonsense. No, it wasn’t ‘narrative discipline,’ it was caring about the accuracy of claims. And no, this wasn’t one isolated error, it was part of a string of errors mostly in the same direction

it’s still illegal to buy the 1963 basket, and that’s central to the argument I’ll make next time.

One other potentially good point Green makes there is that many individuals and couples don’t start families because they don’t feel they can afford one, which biases two-parent household income upwards. But in terms of impact on the averages it’s complicated, because there are kind of two fertility tracks, one for those who are trying to follow the ‘have enough money first’ playbook, and the other where some people go ahead and have kids anyway, and that second group is more present and has higher fertility at lower incomes

I do think that ‘a lot of people don’t have kids because they don’t believe they can afford them’ is central to the problem we face.

…But That’s Not Important Right Now

He then pivots (while continuing to assert various forms of nonsense along the way) into saying ‘the real point’ is two completely distinct other claims that are far better.

Poverty Trap

The first is that phase outs generate a Poverty Trap where effective marginal tax rates can be very high, even in excess of 100%.

That’s a very real, no good, very bad problem.

This, via Jeremy Horpedahl, is the chart that shows a real Valley of Death that can come up under some circumstances

This graph is remarkably terrible. You could plausibly prefer $29k to $69k.

Here’s another graph that goes to the relatively expensive Boston and finds a trap that goes out farther, where you don’t escape until north of $100k:

*Once you get above these thresholds, I don’t want to say you are ‘home free’ but you are strictly better off each time you earn an extra dollar.

Contra Green, ~80% of families of 4 are north of the trap in practice.

Can these dynamics trap people in poverty? Oh yes, absolutely, it’s all quite terrible, and we should work on solutions to make this whole thing sane.

Poverty Trap Versus Poverty Line

However, note that the basic problem will remain, which is:

To live reasonably, people implicitly need ~$50k in total pay and benefits, given the Revolution of Rising Requirements and what you by law have to purchase.

As an intuition pump to how tricky this is, redone from scratch for 2025, for families of exactly 4 only for now: We could change to instead provide a universal basic income (you can also call it a negative income tax) of $40k per family, plus a flat tax of about 25%-35% (depending on implementation details elsewhere) to $250k, then resume the current tax rates (so we don’t change how much we raise from the top of the distribution). No other default benefits, including Medicare and Medicaid, and no other federal taxes (no payroll, no Medicare tax and so on). My quick calculation says that’s roughly revenue neutral. Is that style of approach better? Maybe, but there’s at least one huge obvious problem, which is that this creates unsubsidized health insurance markets with no fallback, and so many others we’re not noticing. Of course, there’s huge upsides, especially if you fix the worst of the secondary effects.

Either way, good luck passing anything like this.

The details Green discusses here are wrong again, including the fragility issue

But here, yes, this part’s very true and important, nail meet head:

The question we are increasingly asking is, “Why aren’t we having more families and procreating?” The answer, largely, is that we are asking families to make an investment in children that becomes a future common good and penalizing them for doing so.

It’s not a new big problem. The story of the world outside of farms has been, roughly, ‘spend your life trying to earn enough money to support as big a family as you can.’

Double or Nothing

As a closing fun note, it can always be worse.

As in: You have to love the community note on this graph.

No, seriously, he took the MIT Living Wage Calculator and doubled it, and considers ‘comfortable’ to include 20% savings while meeting all ‘wants and needs.’ Must be nice.

Okay, good. We got through that. We are now ready for next time.

The $140K Question: Cost Changes Over Time

In The $140,000 Question, I went over recent viral claims about poverty in America.

The calculations behind the claims were invalid, the central claim (that the ‘true poverty line’ was $140k) was absurd, but the terrible vibes are real. People increasingly feel that financial life is getting harder and that success is out of reach.

‘Real income’ is rising, but costs are rising even more.

Before we get to my central explanations for that - the Revolution of Rising Expectations and the Revolution of Rising Requirements - there are calculations and histories to explore, which is what this second post is about.

How are costs changing in America, both in absolute terms and compared to real incomes, for key items: Consumer goods, education, health care and housing?

And how is household wealth actually changing?

The economists are right that the basket of goods and services we typically purchase in these areas has greatly increased in both quantity and quality.

That is not what determines whether a person or family can pay their bills.

The Debate Continues

people talk past each other a lot.

There was an iteration on this back in May, when Curtis Yarvin declared a disingenuous ‘beef’ with Scott Alexander on such questions. A good example of the resulting rhetoric was this exchange between Scott Alexander and Mike Solana.

- Guy will say the cost of a house has more than doubled. He’ll say he can’t afford his home town anymore. The intellectual will make a macro argument with another chart. it will seem smart.

- Guy will still be miserable, his life will still be hard. And he will vote.

Evaluating and often refuting specific claims is a necessary background step. So that’s what this post is here to do. On its own, it’s a distraction, but you need to do it first.

The Cost of Thriving Index Redux

Two years ago I covered the debate around Cass’s Cost of Thriving Index, and the debate over whether the true ‘cost of thriving’ was going up or down.

goods required for ‘thriving’ in each era and then compare combined costs as a function of what a single man can hope to earn, without regard to the rising quality of the basket over time.

The post covered the technical arguments in each area between Winship and Cass. Cass argued that thriving had gotten a lot harder. Winship argued against this.

My conclusion was:

Cass’s calculations were importantly flawed. My ‘improved COTI’ shows a basic basket was ~13% harder for a typical person to afford in 2023 than it was in 1985.

Critics of the index, especially Winship, misunderstood the point of the exercise and in many places trying to solve the wrong problem

This calculation left out at least one very important similar consideration in particular that neither side considered: The time and money costs of not letting kids be kids, and the resulting need to watch them like a hawk at all times, requiring vastly more childcare.

The Housing Theory Of Everything Remains Undefeated

I don’t quite fully buy the Housing Theory of Everything.

But is close.

If you’re okay living where people don’t typically want to live, then things aren’t bad.

However, people are less accepting of that, which is part of the Revolution of Rising Expectations, and opportunity has concentrated in the expensive locations.

Charles Fain Lehman: Americans are unhappy because housing is illegal

**I would instead say, if housing was legal, there would be a lot less unhappiness.

More precisely: If building housing was generally legal, including things like SROs and also massively more capacity in general in the places people want to live, then housing costs would be a lot lower, people would have vastly more Slack, and the whole thing would seem far more solvable.

The median household, with a median income and no outside help, does not by default buy the median house at today’s interest rate. Houses are largely bought with wealth, or owned or acquired in other ways, so by default if you’re relying purely on a median income you’re getting a lot less than the median house.**

But if we suppose you’re a median income earner trying to buy the median house today. If you believe the above graph, it’s going to cost you 70% of your income to make a mortgage payment, plus you’ll need a down payment, so yeah, that’s not going to happen. But that number hasn’t been under 50% in fifty years, so people have long had to find another way and make compromises.

The graph does seem like it has to be understating the jump in recent years, with the jump in mortgage rates, and here’s the Burns Affordability Index

I’m willing to believe that this jump happened, and that some of it is permanent, because interest rates were at historic lows for a long time and we’re probably not going to see that again for a while

Compared to the early 1970s (so when interest rates hadn’t shot up yet) Gale Pooley says a given percentage of household income (counting the shift to two incomes, mind) gets you 73% more house, average size went from 1,634 square feet to 2,614, per person it went from 534 to 1,041, many amenities are much more common (AC, Garage, 4+ bedrooms, etc) and actual housing costs haven’t risen much as a percentage of income.

Things will look worse if you look at the major cities, where there is the most opportunity, and where people actually want to live. This is NIMBY, it is quite bad, and we need to fix it.

That includes increasing unwillingness to live far away from work, and endure what is frankly a rather terrible commute.

Did We Halt the Rise in Healthcare and Education Costs?

For a while a lot of the story of things getting harder was that healthcare and education costs were rising rapidly, far faster than incomes.

Did we turn this around? Noah Smith strongly asserted during the last iteration of the argument that this is solved, the same way the data says that real wages are now accelerating.

The story of healthcare and education goes beyond not getting the discounts on manufactured goods. It extends to a large rise in the amount of goods and services we had to purchase, much of it wasted - Hansonian medicine (over-treated), (college education) academic administrative offices and luxury facilities, credential inflation and years spent mostly on signaling, and so on. Don’t try to pass this all off as Baumol’s Cost Disease.

Noah Smith: If service costs rise relentlessly while manufacturing costs fall, it portends a grim future — one where we have cheap gadgets, but where the big necessities of modern middle-class life are increasingly out of reach. And in fact, that was the story a lot of people were telling in the mid-2010s.

Step back to first principles. This can’t happen purely ‘because cost disease’ unless the total labor demanded is rising.

That only gets harder for you if either:

- The required quality or quantity of [X] or [Y] is rising.

- The cost of a unit of goods is rising relative to incomes.

- The labor you need is rising in cost faster than your own labor.

Which is it?

I assert that the primary problem is that [X] is rising, without much benefit to you.

Why is a class of the same size so much more expensive in units of middle class labor? Noah focuses on higher education later in the post, but as an obvious lower education example: The New York City DOE public school system costs $39k per student. You think that mostly pays for the teachers?

Noah then covers attempts to solve the cost issues via policy,

The solutions he seems to favor here still mainly continue to look a lot like subsidizing demand and using transfers.

Healthcare Costs

But, behold, says Noah. Health care costs have stopped increasing as a percentage of GDP. So Everything Is Fine now, or at least not getting worse. The ways in which he argues things are doing fine helped me realize why things are indeed not so fine here.

This chart represents us spending more on health care, since it’s a constant percentage of a rising GDP. That’s way better than the previous growing percentage. It is still a high percentage and we are unwise to spend so much.

We do not primarily care about how much health care an average American can buy and what it costs them.

We primarily care, for this purpose, about how much it costs in practice to get a basket of health care you are in practice allowed or required to buy.

That means buying, or getting as part of your job, acceptable health insurance.

The systems we have in place de facto require you to purchase a lot more health care services, as measured by these charts. It does not seem to be getting us better health.

As a person forced to buy insurance on the New York (Obamacare) marketplace, I do not notice things getting more affordable. Quite the opposite. If you don’t get the subsidies, and you don’t have an employer, buying enough insurance that you can get even basic healthcare services costs an obscene amount. You can’t opt out because if you do they charge you much higher prices.

There are two ways out of that. One is that if you are sufficiently struggling they give you heavy subsidies, but you only get that if you are struggling, so this does not help you not struggle and is part of how we effectively trap such people in ~100% marginal tax brackets as per the discussions of the poverty trap. Getting constant government emails saying ‘most people on the exchange pay almost nothing!’ threatens to drive one into a blind rage.

The other way is if you have a dayjob that provides you insurance. Securing this is a severe distortion in many people’s lives, which is a big and rising hidden cost. Either way, you’re massively getting distorted, and that isn’t factored in.

The average cost is holding steady as a percentage of income but the uncertainty involved makes it much harder to be comfortable.

It’s not that much worse than it was in the 1990s, but in the 1990s this was (as I remember it) the big nightmare for average people. It isn’t getting better, yet people have other bigger complaints more often now. That’s not a great spot.

Higher Education Costs

I notice that Noah only discusses higher education here. Lower education costs are definitely out of control, including in the senses that:

- Public funding for the schools is wildly higher than the cost of teachers, and wildly higher per student, in ways that don’t seem to help kids learn.

- Public schools are often looking sufficiently unacceptable that people have to opt out even at $0, especially for unusual kids but in many places also in general.

- Private school costs are crazy high when it comes to that.

But sure, public primary and secondary school directly costs $0, so let’s focus on college.

Of course this doesn’t include financial aid (nor does Mark Perry’s chart, nor do official inflation numbers). Financial aid has been going up, especially at private schools. When you include that, it turns out that private four-year nonprofits are actually less expensive in inflation-adjusted terms than they were in the mid-2000s, even without accounting for rising incomes:

I do think people fail to appreciate Noah’s point here, but notice what is happening.

- We charge a giant sticker price.

- We force people to jump through hoops, including limiting their income and doing tons of paperwork to navigate systems, and distort their various life choices around all that, in order to get around the sticker price. (price discrimination)

- If you don’t distort your life they try to eat all your (family’s) money.

- The resulting real price (here net TFHF) remains very high.

I buy the thesis that higher education costs, while quite terrible, are getting modestly better rather than getting worse, for a given amount of higher education

we force people into various hoops including manipulations of family income levels in order to get this effective cost level, which means that the ‘default’ case is actually quite bad.

Services Productivity is Rising But What Even Is Productivity Measuring

Noah’s big takeaway is that services productivity is indeed rising. I notice that he’s treating the productivity statistics as good measures, which I am increasingly skeptical about, especially claims like manufacturing productivity no longer rising? What? How are all the goods still getting cheaper, exactly?

Mostly I see these statistics as reinforcing the story of the Revolution of Rising Requirements.

If services productivity has doubled in the last 50 years, and we feel the need to purchase not only the same quantity of service hours as before but substantially more hours, that makes the situation very clear.

I also would assert that a lot of this new ‘productivity’ is fake in the sense that it does not cash out in things people want. How much ‘productivity’ is going on, for example, in all the new administrative workers in higher education?

This goes hand in hand with the internet and AI showing up everywhere except the productivity statistics. Notice that these graphs don’t seem to bend at all when the internet shows up. We are measuring something useful, but it doesn’t seem to line up well with the amount of useful production going on?

On Clothing In Particular

Alex Tabarrok reminds us that modern clothes are dramatically cheaper.

We spend 3% of income on clothes down from 14% in 1900 and 9% in the 1960s

yes, obviously, the government wanting to ‘bring back apparel manufacturing to America’ is utter madness, this is exactly the kind of job you want to outsource.

Our Price Free

Related to all this is the question of how much we benefit from free goods? A (gated) paper attempts to quantify this with GDP-B, saying ‘gains from Facebook’ add 0.05%-0.11% to yearly welfare growth and improvements in smartphones add 0.63%. Which would be a huge deal.

Both seem suspiciously high.

By Default Supply Side Is The Problem

Tyler Cowen: Most of all, there is a major conceptual error in Green’s focus on high prices. To the extent that prices are high, it is not because our supply chains have been destroyed by earthquakes or nuclear bombs.

Rather, prices are high in large part because demand is high, which can only happen because so many more Americans can afford to buy things.

I challenge. This is not primarily a demand side issue.

Over time supply should be elastic. Shouldn’t we assume we have a supply side issue?

Where is this not mostly a self-inflicted wound?

The answer to that is positional goods. Saying ‘look at how much more positional goods everyone is buying’ is not exactly an answer that should make anyone happy. If everyone is forced to consume more educational or other signaling, that’s worse.

The biggest causes of high prices on non-positional goods are supply side restrictions, especially on housing and also other key services with government restrictions on production and often subsidized or mandated demand to boot.

Supply tends to be remarkably elastic in the medium term, why is that not fixing the issue? If we’re so rich, why don’t you increase production? Something must be preventing you from doing so.

Often the answer is indeed supply restrictions. In some of the remaining cases you can say Baumol’s Cost Disease. In many others, you can’t. Or you can partially blame Baumol but then you have to ask why we need so much labor per person to produce necessary goods. It’s not like the labor got worse.

The burdens placed are often part of the Revolution of Rising Requirements.

Americans buying lots of things is good, but it does not impact how hard it is to make ends meet.

It is not a conceptual error to then focus on high prices, if prices are relevantly high.

It is especially right to focus on high prices if quality requirements for necessary goods have been raised, which in turn raised prices.

The Kids Are Financially Alright In Historical Terms

The latest news is that Millennials, contrary to general impressions, are now out in front in ‘real dollar’ terms for both income and wealth, and their combined spending on housing, food and clothing continues to decline as a percentage of income

The bad news is that if you think of wealth as a percentage of the cost of a house, then that calculation looks a lot worse.

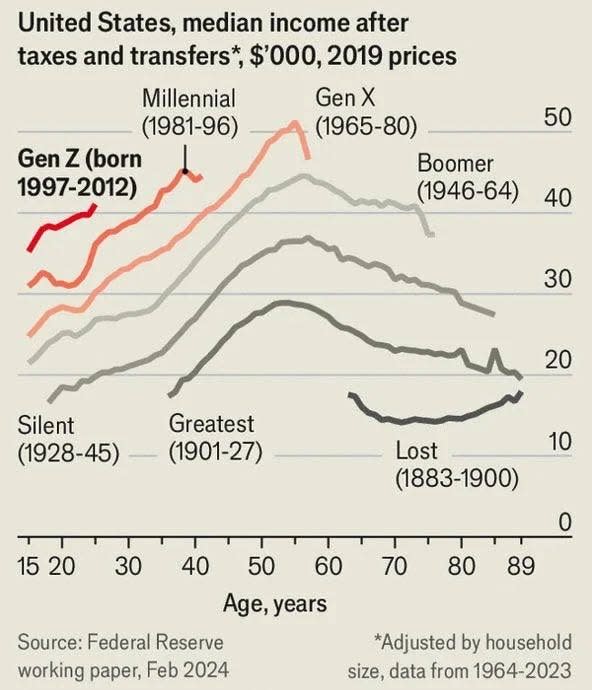

Similarly, this is the classic graph on income, adjusted for inflation, after taxes and transfers, showing Gen Z is making more money:

Jeremy Horpedahl: The share of income spent on food, clothing, and housing in the has declined dramatically since 1901 in the United States. It’s even lower than in 1973, which many claim is the beginning of economic stagnation

I strongly believe the numbers are right. One must then figure out what that means.

Live Like a Khan

Are you more wealthy than a khan?

Ben Dreyfuss: So many tweets on this website are people describing the almost unimaginable level of comfort and prosperity enjoyed in this country and then being like “but it sucks” haha

I instead say: It is obviously true in a material wealth and comfort sense excluding ability to find companions or raise children, and no one believes it because that’s not the relevant comparison and they’re not drawing the distinction precisely

Yes, in terms of material goods in an absolute sense you are vastly richer than the Khans

once again, your material wealth will still struggle to support a family and children, or to feel secure and able to not stress about money, and most people feel constrained by money in how many children they can have. (precarity)

We Should Be Doing Far Better On All This

Guy’s life should be easier. Why isn’t it?

My answer, the thing I’m centrally building towards, is that this doesn’t represent the full range of costs and cost changes, centrally for two reasons: The Revolutions of Rising Expectations and Rising Requirements.

When Were Things The Best?

People remember their childhood world too fondly. You adapt to it. You forget the parts that sucked, many of which sucked rather really badly. It resonates with you and sticks with you. You think it was better

This is famously true for music, but also in general, including places it makes no sense like ‘most reliable news reporting.’

As a fun and also useful exercise, as part of the affordability sequence, now that we’ve looked at claims of modern impoverishment and asked when things were cheaper, it’s time to ask ourselves: When were various things really at their best?

In some aspects, yes, the past was better, and those aspects are an important part of the picture. But in many others today is the day and people are wrong about this.

The Most Close-Knit Communities

Far in the past. You wouldn’t like how they accomplished it, but they accomplished it. (Communities That Abide)

You’re not going to match that without making intensive other sacrifices. Nor should you want to. Those communities were too close-knit for our taste.

Close-knit communities, on a lesser level that is now rare, are valuable and important, but require large continuous investments and opportunity costs. (intentional community)

Intentional communities are underrated, as is simply coordinating to live near your friends. I highly recommend such things, but coordination is hard, and they are going to remain rare.

The Most Moral Society

I’m torn between today and about 2012.

There are some virtues and morals that are valuable and have been largely lost. Those who remember the past fondly focus on those aspects.

One could cite, depending on your comparison point, some combination of loyalty to both individuals... (Long list)

But they pale in comparison to the ways that things used to be terrible. People used to have highly exclusionary circles of concern. By the standards of today, until very recently and even under relatively good conditions, approximately everyone was horribly violent and tolerant of violence and bullying of all kinds, cruel to animals, tolerant of all manner of harassment

It should be very clear which list wins.

This holds up to the introduction of social media, at which point some moral dynamics got out of control in various ways, on various sides of various questions, and many aspects went downhill.

The Least Political Division

Within recent memory I’m going to say 1992-1996, which is the trap of putting it right in my teenage years. But I’m right. This period had extraordinarily low political division and partisanship.

On a longer time frame, the correct answer is the Era of Good Feelings, 1815-1825.

The Happiest Families

Good question. The survey data says 1957.

I also don’t strongly believe it is wrong, but I don’t trust survey data to give the right answer on this, for multiple reasons.

Certainly a lot more families used to be intact. That does not mean they were happy by our modern understanding of happy. The world of the 1950s was quite stifling

The Most Reliable News Reporting

Believe it or not, today. Yikes. We don’t believe it because of the Revolution of Rising Expectations. We now have standards for the press that the press has never met.

that loss of trust is centrally good. The media was never worthy of trust.

There’s great fondness for the Walter Cronkite era

that past trust was also misplaced, and indeed was even more misplaced.

If your goal is to figure out what is going on and you’re willing to put in the work, today you have the tools to do that, and in the past you basically didn’t, not in any reasonable amount of time.

The fact that other people do that, and hold them to account, makes the press hold itself to higher standards.

The Best Music

There are several forms of ‘the best music.’ It’s kind of today, kind of the 60s-80s.

If you are listening to music on your own, it is at its best today, by far. The entire back catalogue of the world is available at your fingertips

If you want to create new music, on your own or with AI? Again, it’s there for you.

In terms of the creation of new music weighted by how much people listen, or in terms of the quality of the most popular music, I’d say probably the 1980s? A strong case can be made for the 60s or 70s too, my guess is that a bunch of that is nostalgia and too highly valuing innovation, but I can see it.

In terms of live music experiences, especially for those with limited budgets, my guess is this was closer to 1971, as so much great stuff was in hindsight so amazingly accessible.

The Best Radio

My wild guess for traditional radio is the 1970s? There was enough high quality music, you had the spirit of radio, and video hadn’t killed the radio star.

You could make an argument for the 1930s-40s, right before television displaced it as the main medium.

The real answer is today. We have the best radio today.

We simply don’t call it radio.

Instead, we mostly call it podcasts and music streaming.

The Best Fashion

Long before any of us were born, or today, depending on whether you mean ‘most awesome’ or ‘would choose to wear.’

The Best Economy

As the question is intended, 2019. Then Covid-19 happened. We still haven’t fully recovered from that.

There were periods with more economic growth or that had better employment conditions. You could point to 1947-1973 riding the postwar wave, or the late 1990s before the dot com bubble burst.

I still say 2019, because levels of wealth and real wages also matter.

The Best Movies

In general I choose today. Average quality is way up and has been going up steadily except for a blip when we got way too many superhero movies crowding things out, but we’ve recovered from that.

The counterargument I respect is that the last few years have had no top tier all-time greats, and perhaps this is not an accident.

If I have to pick a particular year I’d go with 1999.

The traditional answer is the 1970s, but this is stupid and disregards the Revolution of Rising Expectations. Movies then were given tons of slack in essentially every direction

The Best Television

*Today. Stop lying to yourself.

The experience of television used to be terrible, and the shows used to be terrible. So many things very much do not hold up today even if you cut them quite a lot of slack. Old sitcoms are sleep inducing. Old dramas were basic and had little continuity. Acting tended to be quite poor. They don’t look good, either.*

The alternative argument to today being best is that many say that in terms of new shows the prestige TV era of the 2000s-2010s was the golden age, and the new streaming era can’t measure up, especially due to fractured experiences.

I agree that the shared national experiences were cool and we used to have more of them and they were bigger. We still get them, most recently for Severance and perhaps The White Lotus and Plurebis, which isn’t the same, but there really are still a ton of very high quality shows out there.

Best Sporting Events

Today. Stop lying to yourself.

Average quality of athletic performance is way, way up.

The Best Cuisine

Today, and it’s really, really not close. If you don’t agree, you do not remember. So much of what people ate in the 20th century was barely even food by today’s standards, both in terms of tasting good and its nutritional content.

A lot of this is driven by having access to online information and reviews, which allows quality to win out in a way it didn’t before, but even before that we were seeing rapid upgrades across the board.

Bonus: The Best Job Security

Some time around 1965, probably? We had a pattern of something approaching lifetime employment where it was easy to keep one’s job for a long period, and count on this. The chance of staying in a job for 10+ or 20+ years has declined a lot. That makes people feel a lot more secure, and matters a lot.

That doesn’t mean you actually want the same job for 20+ years.

The Best Everything

We don’t have the best everything. There are exceptions.

But there are so many other places in which people are simply wrong.

As in:

Matt Walsh (being wrong, lol at ‘empirical,’ 3M views): It’s an empirical fact that basically everything in our day to day lives has gotten worse over the years.

My quick investigation confirmed that American roads, traffic and that style of infrastructure did peak in the mid-to-late 20th century. We have not been doing a good job maintaining that.

On food, entertainment, clothing and housing he is simply wrong

I am begging somebody to name 1 thing that is all around a better product than its counterpart from the 90s.

Megan McArdle: Tomatoes, raspberries, automobiles, televisions, cancer drugs, women’s shoes, insulin monitoring, home security monitoring, clothing for tall women (which functionally didn’t exist until about 2008), telephone service (remember when you had to PAY EXTRA to call another area code?), travel (remember MAPS?), remote work, home video

The Best Information Sources, Electronics, Medical Care, Dental Care, Medical (and Non-Medical) Drugs, Medical Devices, Home Security Systems, Telephone Services and Mobile Phones, Communication, and Delivery Services of All Kinds Today. No explanation required on these.

Saying the quality of phones has gone down, as Matt Walsh does, is absurdity.

That does still leave a few other examples he raised.

The Best Air Travel

*Today, or at least 2024 if you think Trump messed some things up.

I say this as someone who used to fly on about half of weekends, for several years.*

Air travel has decreased in price, the most important factor, and safety improved.

The Best Cars

Today. We wax nostalgic about old cars. They looked cool. They also were cool.

They were also less powerful, more dangerous, much less fuel efficient, much less reliable, with far fewer features and of course absolutely no smart features.

The Best Roads, Traffic and Infrastructure

This is one area where my preliminary research did back Walsh up. America has done a poor job of maintaining its roads and managing its street traffic

As a result of not keeping up with demand for roads or demand for housing in the right areas, average commute times for those going into the office have been increasing, but post-Covid-19 we have ~29% of working days happening from home, which overwhelms all other factors combined in terms of hours on the road.

The Best Transportation

Today, or at least the mobile phone and rideshare era. You used to have to call for or hail a taxi. Now in most areas you open your phone and a car appears.

This is way more important than net modest issues with roads and traffic.

Trains have not improved but they are not importantly worse.

It’s Getting Better All The Time

Not everything is getting better all the time. Important things are getting worse.

We still need to remember and count our blessings, and not make up stories

the following things did indeed peak in the past and quality is getting worse as more than a temporary blip:

- Political division.

- Average quality of new music, weighted by what people listen to.

- Live music and live radio experiences, and other collective national experiences.

- Fashion, in terms of awesomeness.

- Roads, traffic and general infrastructure.

- Some secondary but important moral values.

- Dating experiences, ability to avoid going on apps.

- Job security, ability to stay in one job for decades if desired.

- Marriage rates and intact families, including some definitions of ‘happy’ families.

- Fertility rates and felt ability to have and support children as desired.

- Childhood freedoms and physical experiences.

- Hope for the future, which is centrally motivating this whole series of posts.

The second half of that list is freaking depressing. Yikes. Something’s very wrong.

But what’s wrong isn’t the quality of goods, or many of the things people wax nostalgic about. The first half of this list cannot explain the second half.

many of these cases things are 10 times better, or 100 times better, or barely used to even exist:

- Morality overall, in many rather huge ways.

- Access to information, including the news.

- Logistics and delivery. Ease of getting the things you want.

That only emphasizes the bottom of the first list. Something’s very wrong.

We Should Be Doing Far Better On All This

the changes in quantity and quality of goods and services do not explain people’s unhappiness, or why many of the most important things are getting worse. More is happening.

That more is what I will, in the next post, be calling The Revolution of Rising Expectations, and the Revolution of Rising Requirements

The Revolution of Rising Expectations

Internet arguments like the $140,000 Question incident keep happening.

The two sides say:

Life sucks, you can’t get ahead, you can’t have a family or own a house.

What are you talking about, median wages are up, unemployment is low and so on.

The economic data is correct. Real wages are indeed up. Costs for food and clothing are way down while quality is up, housing is more expensive than it should be but is not much more expensive relative to incomes.

But that does not tell us that buying a socially and legally acceptable basket of goods for a family has gotten easier, nor that the new basket will make us happier.

This post is my attempt to reconcile those perspectives.

The culprit is the Revolution of Rising Expectations, together with the Revolution of Rising Requirements.

The biggest rising expectations are that we will not have to tolerate unpleasant experiences or even dead time, endure meaningful material shortages or accept various forms of unfairness or coercion.

The biggest rising requirement is insane levels of mandatory child supervision. (childcare)

Table of Contents

- The Revolutions of Rising Expectations.

- The Revolution of Rising Requirements.

- Whose Line Is It Anyway?

- Thus In This House We Believe The Following.

- Real De Facto Required Expenses Are Rising Higher Than Inflation.

- Great Expectations.

- We Could Fix It.

- Man’s Search For Meaning.

- How Do You Afford Your Rock And Roll Lifestyle?

- Our Price Cheap.

- It Takes Two (1).

- It Takes Two (2).

- If So, Then What Are You Going To Do About It, Punk?

- The Revolution of Rising Expectations Redux.

The Revolutions of Rising Expectations

Our negative perceptions largely stem from the Revolution of Rising Expectations.

We find the compromises of the past simply unacceptable.

This includes things like:

- Jobs, relationships and marriages that are terrible experiences.

- Managing real material shortages.

- Living in cash-poor ways to have one parent stay at home.

These are mostly wise things to dislike. They used to be worse. That was worse.

Not that most people actually want to return. Again, Rising Expectations

Doing this requires you to earn that ‘normal income’ from a small town in the midwest, which is not as easy, and you have to deal with all the other problems. If you can pull off this level of resisting rising expectations you can then enjoy objectively high material living standards versus the past. That doesn’t solve a lot of your other problems. It doesn’t get you friends who respect you or neighbors with intact families who watch out for your kids rather than calling CPS.

Is the 2025 basket importantly better? Hell yes. That doesn’t make it any easier to purchase the Minimum Viable Basket.

The Revolution of Rising Requirements

In addition to the demands that come directly from Rising Expectations, there are large new legal demands on our time and budgets. Society strongarms us to buy more house, more healthcare, more child supervision and far more advanced technology

The killer requirement, where it is easy to miss how important it is, is that we now impose utterly insane child supervision requirements on parents and the resulting restrictions on child freedoms, on pain of authorities plausibly ruining your life for even one incident. (childcare, free-range kids)

This includes:

- A wide variety of burdensome requirements on everyday products and activities, including activities that were previously freely available.

- Minimum socially and often legally acceptable housing requirements.

Forced interactions with a variety of systems that are Out To Get You.

The replacement of goods that were previously socially provided, but which now must be purchased, which adds to measured GDP but makes life harder

Nor if you pulled this off would you enjoy the social dynamics required to support such a lifestyle. You’d get CPS called on you, be looked down upon, no one would help watch your kids or want to be your friends or invite you to anything.

Whose Line Is It Anyway?

A rule for game designers is that:

- When a player tells you something is wrong, they’re right. Believe them.

- When a player tells you what exactly is wrong and how to fix it? Ignore them.

- Still register that as ‘something is wrong here.’ Fix it.

As in, I actually disagree with this, as a principle:

- Matthew Yglesias: Some excellent charts and info here, but I think the impulse to sanewash and “clean up” false claims is kind of misguided.

If we want to address people’s concerns, they need to state the concerns accurately.

No. If you want to address people’s concerns rather than win an argument, then it is you who must identify and state their concerns accurately.

What you definitely do not want to do is accept the false dystopian premise that America, the richest large country in human history, has historically poor material conditions.

Brad: A lot of folks seem think they are going to bring radicalized young people back into the fold by falsely conceding that material conditions in the most advanced, prosperous country in the history of the world are so bad that it’s actually reasonable to become a nihilistic radical.

Thus In This House We Believe The Following:

We live in an age of wonders that in many central ways is vastly superior.

I strongly prefer here to elsewhere and the present to the past.

- It is still very possible to make ends meet financially in America.

- *Real median wages have risen.

However, due to rising expectations and rising requirements:

- The cost of the de facto required basket of goods and services has risen even more.

- Survival requires jumping through costly hoops not in the statistics.

- We lack key social supports and affordances we used to have.

- You cannot simply ‘buy the older basket of goods and services.’

- Staying afloat, ‘making your life work,’ has for a while been getting harder.

This is all highly conflated with ‘when things were better’ more generally.

Real De Facto Required Expenses Are Rising Higher Than Inflation

the voters are not wrong. The practical ‘cost of living’ has gone up.

Here’s a stark statement of much of this in its purest form, on the housing front.

Aella: being poorer is harder now than it used to be because lower standards of living are illegal. Want a tiny house? illegal. want to share a bathroom with a stranger? illegal. The floor has risen and beneath it is a pit.

Great Expectations

The two Revolutions combine to make young people think success is out of reach.

This leads them to forget that young people have always been poor on shoestring budgets. The young never had it easy in terms of money. Past youth was even poorer, but were allowed (legally and socially) to economize far more.

When the debate involves people near or above the median, the boomers have a point. If you make ~$100k/year and aren’t in a high cost of living area (e.g. NYC, SF), you are successful, doing relatively well, and will be able to raise a family on that single income while living in many ways far better than it was possible to live 50 years ago.

There’s also this: People reliably think they are poorer, in relative terms, than they are, partly due to visibility asymmetry and potentially geographic clustering, and due to the fatness of the right tail having an oversize impact.

These perceptions have real consequences. Major life milestones like marriage and children get postponed, often indefinitely. Young people, especially young men, increasingly feel compelled to find some other way to strike it rich, contributing to the rise of gambling, day trading, crypto and more

We Could Fix It

We could choose to, without much downside:

- Make housing vastly cheaper especially for those who need less.

- Make childcare vastly less necessary and also cheaper, and give children a wide variety of greater experiences for free or on the cheap.

- Make healthcare vastly cheaper for those who don’t want to buy an all-access pass.

- Make education vastly cheaper and better.

- Make energy far more abundant and cheap, which helps a lot of other things.

The bad news is there is no clear path to our civilization choosing to fix these errors, although every marginal move towards the abundance agenda helps.

We could also seek to strengthen our social and familial bonds, build back social capital and reduce atomization, but that’s all much harder. There’s no regulatory fix for that.

Man’s Search For Meaning

Matt Yglesias points out that this goes hand in hand with Americans putting less value on things money can’t buy:

A nice thing about valuing religion, kids, and patriotism is that these are largely non-positional (status) goods that everyone can chase simultaneously without making each other miserable.

This change in values is not good for people’s life experience and happiness. If being happy with your financial success requires you to be earning and spending ahead of others, and it becomes a positional good, then collectively we’re screwed.

There were ways in which I did not ‘feel’ properly successful until I stopped renting and bought an apartment, despite the decision to previously not buy being sensible and having nothing to do with lack of available funds. Until you say ‘this house is mine’ things don’t quite feel solid.

Many view ‘success’ as being married and owning a home, regardless of total wealth.

So this chart seems rather scary:

That leads to widespread expressions of (highly overstated) hopelessness:

Boring Business: An entire generation under the age of 30 is coming to realization that having a family and home will never be within the grasp of reality for them

Another issue is that due to antipoverty programs and subsidies and phase outs, as covered last time, including things not even covered there like college tuition, the true marginal tax rate for families is very high when moving from $30k to up to ~$100k.

How Do You Afford Your Rock And Roll Lifestyle?

Social media and influencing make all of this that much worse. We’re up against severe negativity bias and we’re comparing ourselves to those who are most successful at presenting the illusion of superficial success.

Timothy Lee: I think this #5 here is an important reason why so many people feel beleaguered. People’s expectations for what “counts” as a middle-class standard of living is a lot higher than in previous generations, and so they feel poor even if they are living similarly.

Beyond social media, I think another factor is that people compare their parents’ standard of living at 55 with their own standard of living at 25 or whatever. Nobody remembers how their parents lived before they were born

two groups of loadbearing mechanisms raised here on top of the general Revolutions of Rising Expectations and Requirements arguments earlier.

- Negativity bias alongside Rising Expectations for lifestyle in social media, largely due to it concentrating among expensive cities with dysfunctional housing markets.

- Post-Covid inflation, right after a brief period of massive subsidies to purchasing power.

Our Price Cheap

There are also real problems, as I will address later at length, especially on home ownership and raising children. Both are true at once.

Want to raise a family on one median income today? You get what you pay for.

Will Ricciardella: Can a family live on one income today?

Yes, but not today’s lifestyle on yesterday’s budget.

Here’s what it actually looks like

It is always interesting to see what such lists want to sacrifice. A lot of the items above are remarkably tiny savings in exchange for big hits to lifestyle. In others, they do the opposite. People see richer folks talking to them like this, and it rightfully pisses them off.

- No microwave? To save fifty bucks once and make cooking harder? What?

- No A/C is in many places in America actively dangerous.

It Takes Two (1)

Thus, people increasingly believe they need two incomes to support a family. (two-income family)

First, some brief questions worth asking in advance:

Can you actually execute on the one income plan?

If not, what are you going to do about it?

It Takes Two (2)

Even if you could somehow execute on the above plan to survive on one income by having life suck in various ways, that plan also takes two.

Not two incomes. Two parents.

Hey baby, want to live on one income, Will Ricciardella style? Hey, come back here. (dating market)

Telling young men in particular ‘you can do it on one income’ via this kind of approach is a joke, because try telling the woman you want to marry that you want to live in the style Will Ricciardella describes above. See if she says yes.

If So, Then What Are You Going To Do About It, Punk?

If you want one income households and stay at home parents to be viable here, I would say four things are required, in some combination. You don’t need all four, but you definitely need #1, and then some additional help.

You can deal with the Requirements. Let people purchase much less health care, child care and housing. Give people a huge amount of Slack, such that they can survive on one income despite the ability to earn two, and also pay for kids.

You can deal with the Expectations. Raise the status and social acceptability of living cheap and making sacrifices.

I usually discuss these issues and questions, especially around #4, in terms of declining fertility. It is the same problem. If people don’t feel able to have children in a way they find acceptable, then they will choose not to have children.

Alternatively or additionally, from a policy perspective, you can accept that you’re looking at two income households, and plan the world around making that work.

The big problem with a two income household is child supervision.

Now, back to the question of what is going on.

The Revolution of Rising Expectations Redux

The definition of ‘necessity’ is not a constant, as the linked post admits. The ‘necessities’ that have gotten cheaper are the ‘necessities of the past.’ If things like education and health care and cell phones are de facto mandatory, and you have to buy them, then they are now necessities, even if in 1901 the services in question flat out didn’t exist.

what do we do about it?

It’s tough to lower the Rising Expectations. We should still do what we can here, primarily via cultural efforts, in the places we can do that.

Rising Requirements are often unforced errors. We Can Fix It. We should attack. If we legalized housing, and legalized passing up Hansonian medicine (over-treated), and got to a reasonable place on required child supervision (free-range kids), that would do it.

Pay Parents Money. Children are a public good, and we are putting so much of the cost burden directly on the parents.

Reforming our system of transfers and benefits and taxes to eliminate the Poverty Trap, such that no one ever faces oppressive marginal tax rates or incentives to not work, and we stop forcing poor families to jump through so many hoops.

All other ways of improving things also improve this. Give people better opportunities, better jobs, better life experiences, better anything, and especially better hope for the future in any and all ways.

Edited: | Tweet this! | Search Twitter for discussion

Made with flux.garden

Made with flux.garden